Hespeler, 14 October, 2018 © Scott McAndless

John 20:19-29, Acts 20:7-12, Psalm 16:1-11

| I |

f there is one thing you need to know about Simon, it is this. He loves Apple. I’m not talking about the fruit here; I’m talking about the company. Simon doesn’t just like Apple products, Simon doesn’t just exclusively use Apple products. Apple products give meaning to his entire life.

I mean, you probably know some people who always have the latest and greatest model of the iPhone®, who you never see without the ends of Apple Earpods® hanging out of their ears, who do all of their work on a Macbook Pro®, read and create with an iPad® and an Apple Pencil®, but I’m not just talking about that. For Simon that is only the beginning. He does that almost without having to think about it.

No, Simon goes out of his way to make sure that every part of his life bears the Apple logo on it. His entire home is run by his HomePod®. Any appliance that is not able to connect to it is not the kind of appliance that Simon wants to have. Any television show that is not available on AppleTV® is a show that Simon doesn’t need to watch. Simon doesn’t have a life, he has iLife® and that is good enough for him. That’s Simon. If you know that about Simon, you will know everything there is to know. You will know how he will react in every situation because he will do whatever Siri® tells him to do. He once drove into a ditch because Apple Maps® told him to.

Do you know a Simon? I have known a few. And if you don’t know someone who is that big of a fan of Apple products, maybe you know a fan of some other brand: Honda, Nike or maybe Tim Hortons. So, if you don’t know Simon, just imagine for a moment that you do. Can you see him there – wearing his Apple Watch®, Think Different® t-shirt, sporting a tattoo of an apple with one bite out of it? You know the type.

So let’s say you know a Simon. You know that Apple is the organizing principle of his life until one day it isn’t. Yes, one day Simon comes along holding an Android phone and tells you that he is now Android all the way. What would you think? Wouldn’t you assume that something serious – maybe even earth shattering – had happened in Simon’s life to make such a radical change? You might not know what, of course. Maybe he had his iPhone® explode in his hand or maybe he had an Android phone literally save his life. You might not know what, but you would know with certainty that something undeniable had happened.

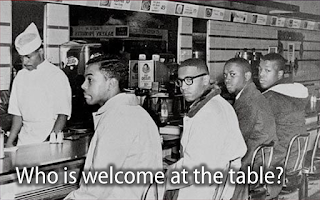

Okay, now consider this. You have eleven guys – just them and a few of their friends – that you have always known one thing about. Most of the time they are pretty normal people. They work, they play, they eat with a few strange habits but they are just regular folks. But there is this one odd thing about them. One day a week they treat completely differently.

I’m not just saying that they take that day off (which is in itself a pretty extraordinary thing in our 24 hour seven days a week world). It’s that that day is completely different for them. They won’t do anything. If the fire goes out in their house, they won’t even relight it. They get on an elevator that day, and they won’t even press the button to say which floor they want to get off on. They are just freakishly strange about this day, so much so that the way that they keep that day gives meaning and definition to their entire week. You might even say that the way they keep that day gives definition and meaning to their entire life. That is how significant it is to them. That day of the week, by the way, is Saturday.

And then, one day, you run into them and everything has changed. All of a sudden, they don’t care about Saturday at all. It is just another day for them. All of a sudden it’s all about Sunday. Sunday is the day that means the world to them and that gives meaning to their entire week and their entire lives. You’ve got to figure that something very important and undeniable happened to them on a Sunday.

That is the quandary we have when we look at the early Christian movement. The early Christian Church, in the years following the death of Jesus, was entirely made up of Jews. And, as Jews, these were people for whom the keeping of the seventh day of the week, Saturday, meant everything. It wasn’t just a day off for them, it was, as I have portrayed, an observance that gave meaning to their entire existence. And yet the evidence clearly indicates that, all of a sudden, all of these Jews just stopped observing the Sabbath. Saturday suddenly meant almost nothing to them. And instead, it was suddenly all about an entirely different day of the week; it was all about Sunday.

People don’t do that, don’t make that kind of radical change, without a very good reason. You have to assume that something happened to them, something very powerful, that made them look at the entire week and at their entire lives in a very different way.

So, the obvious question when you look at the early church is this, what happened? The short answer to that question, as explained in our reading from the Catechism this morning, is the resurrection. Jesus rose from the dead on a Sunday. That is the one thing that changed everything for the church. In fact, I happen to believe that perhaps the greatest evidence we can present for the reality of the resurrection of Jesus is that that is about the only way we can possibly explain why a bunch of Jews would make such a drastic change in their lives. Only something as extraordinary as a resurrection could have convinced them to do that.

But I know how we usually think of that. We think of the resurrection as a one-time event. It only happened on one Sunday, Easter Sunday. But I am not sure that the early Christians experienced it exactly like that.

This morning we read the accounts of three Sundays in the life of the early church. The first Sunday that we read about, in the Gospel of John, was, of course, a story of Easter Sunday. “When it was evening on that day (that is, Easter day), the first day of the week (that is, Sunday), and the doors of the house where the disciples had met were locked for fear of the Jews...” So what we have in this passage is the church, in the form of the disciples gathered together, on a Sunday. And when the church is gathered in this way, they have an experience of the Risen Christ. “Jesus came and stood among them and said, ‘Peace be with you.’”

I realize that you’re going to tell me that there is nothing very extraordinary about that. It’s Easter! Of course the disciples had an experience of the Risen Christ; that’s what Easter is about. But stay with me a moment here because I don’t think the gospel writer is quite done in his explanation of what the church really experienced, because what is the very next thing that he says?

“A week later his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them.”[1] so we jump immediately to the next Sunday, the next meeting of the church, as if nothing significant has happened in the meantime. And, indeed, I think that John is saying that nothing has happened. I think it’s important for John to say that the church next experienced the risen Jesus when they gathered again on a Sunday.

There are other stories of the church meeting with Jesus after his death that happened on Sundays. There’s one at the end of the Gospel of Luke where two disciples are walking along on a Sunday and are joined by a third who explains the scriptures to them and then all three sit down to share a meal and, when the stranger breaks the bread, the others suddenly recognize that the risen Jesus is among them. That also is a description of the early church meeting on a Sunday where two or three are gathered, the scriptures are preached and bread is broken. That gospel writer, Luke, is also saying that this was the regular Sunday experience of the early church.

We read one more story how about the church gathering on Sunday this morning. This one happens many years later as told in the book of Acts, but everything in this story sounds very familiar. It’s Sunday, the church comes together to break bread, and there’s even a preacher there to preach a sermon. In fact, in a way that no doubt resonates with many Christians down through the centuries, there is a preacher who has a tendency to preach a little bit long. I mean, I’m sure that nobody in the entire history of this church has ever thought the sermon was too long so maybe you can’t relate to that, but I have heard that many Christians do think that sometimes. So we have it all, a Sunday gathering, breaking bread or communion, and a really, really long sermon. It is a stereotypical Sunday church meeting that Christians from down through the ages would recognize.

But there is one truly extraordinary element in this Sunday meeting as told in the Book of Acts. It happens when Eutychus falls asleep while Paul drones on and on. He plunges from the third-story window apparently to his death. What is important about that story? Is it just another great miracle story among many miracle stories in the book of Acts? No, I think there’s something special about this one because it happens when the church is gathered on Sunday.

The writer tells his story very carefully at this point. He doesn’t say that Eutychus is actually dead, merely that everyone thinks that he’s dead. And when Paul comes along he doesn’t explicitly say that Paul raises the dead boy to life. It could be that Paul is saying that the others are merely mistaken in thinking that the boy is dead. The author avoids saying in so many words that it is a resurrection miracle, but he certainly gets across the point that the church experienced it as a miracle. The emphasis is certainly on their experience and feelings in the last phrase, “Meanwhile they had taken the boy away alive and were not a little comforted.”

I think that this is the author’s way of saying that, even many years after the first Easter, the church was still experiencing the power and reality of the resurrection of Jesus when they gathered on Sundays – in this case, of course, experiencing it very practically in the salvation of Eutychus.

I’m not saying that it happened so dramatically every week, of course, but I would say that the New Testament writers are in agreement that the experience of the risen Christ was not just limited to one Sunday or just to a short period of time. It was something that kept on happening over and over again each Sunday as the church continued to meet, to pray, to listen to scriptures and break bread, they discovered the risen Jesus among them in many ways.

It didn’t only happen on Sundays, of course. I have no doubt that there were some pretty amazing experiences that happened on other days of the week. But it was on Sundays, when they gathered, that it happened most consistently and reliably for the early church. And that is the only thing that can really explain how a bunch of Saturday fanboys were willing to change everything that they had ever been and had ever told them who they were to suddenly start treating Sunday like it was the only day that truly mattered.

But here’s is the thing: it doesn’t just need to be them. Our Lord Jesus Christ, crucified by Pilate so long ago, is nevertheless still just as alive today as he was for the early church. If they consistently experienced the power of his resurrection week after week when they gathered, then why wouldn’t we? The bottom line is that there is no reason why we shouldn’t. Indeed, I know that it still happens sometimes. I have experienced it myself and I have heard of the experiences of many others. Such experiences are a gift of God, come in many forms, and they are received (like all of God’s gifts) by faith. There is no reason why you should not be able to have such an experience of the risen Jesus.

In fact, I would suggest that the main reason why it doesn’t happen more is because we have largely convinced ourselves not to expect it. In our stubbornness, we have closed ourselves off from the experience by the ways in which we are always rationalizing everything, focusing on the negative and trying to keep control of everything. But just think if you, like those early Christians, were to approach each Sunday with an overwhelming expectation – if you were to walk into church each week not knowing where you would find the risen Jesus (perhaps in a reading or in a word that was shared, perhaps in a beautiful piece of music, in the face of your neighbour, perhaps even in a piece of bread and a cup of wine), but knowing that he would be there for you. Maybe you would also learn the true meaning of Sunday.

[1] Some translations here have “Eight days later.” It is true that that is what the original Greek text says, but, in the context, the first Sunday seems to be counted as the first day, eight days later would mean the next Sunday. I believe this translation is correct.